_ _ _ _

__/\\___ _ /\\ __/\\___ /\\__

(_ ____)) /\\ / //(_ ____)) / \\

+ --------------- / ._)) \ \/ // / ._)) _\ \_// ---------------- +

| /:. ||___ _\:.// /:. ||___ // \:.\ |

| \ _____))(_ _)) \ _____))\\__ / |

| \// \// \// \\/ |

| |

| |

| |

| As we strive towards this ideal image of the perfect observer, |

| we run away from anything less than what may paint us as unyielding |

| angels, saints, and now cyborg patriots of objectivity. |

| |

| |

| |

| |

+____________________________________________________________________________ +

Our bodies and minds are wired to observe. To do almost anything is to have observed some iteration of it before. Even in action, our bodies ceaselessly gather sensory information to inform us as life renders before us.

We are creatures of input.

The mind stirs with a lifetime of information. A weight so heavy upon our shoulders: As natural as it is to take input, it is just as natural to express outward. To gesture, to talk, to draw, to write, to document.

We are creatures of output.

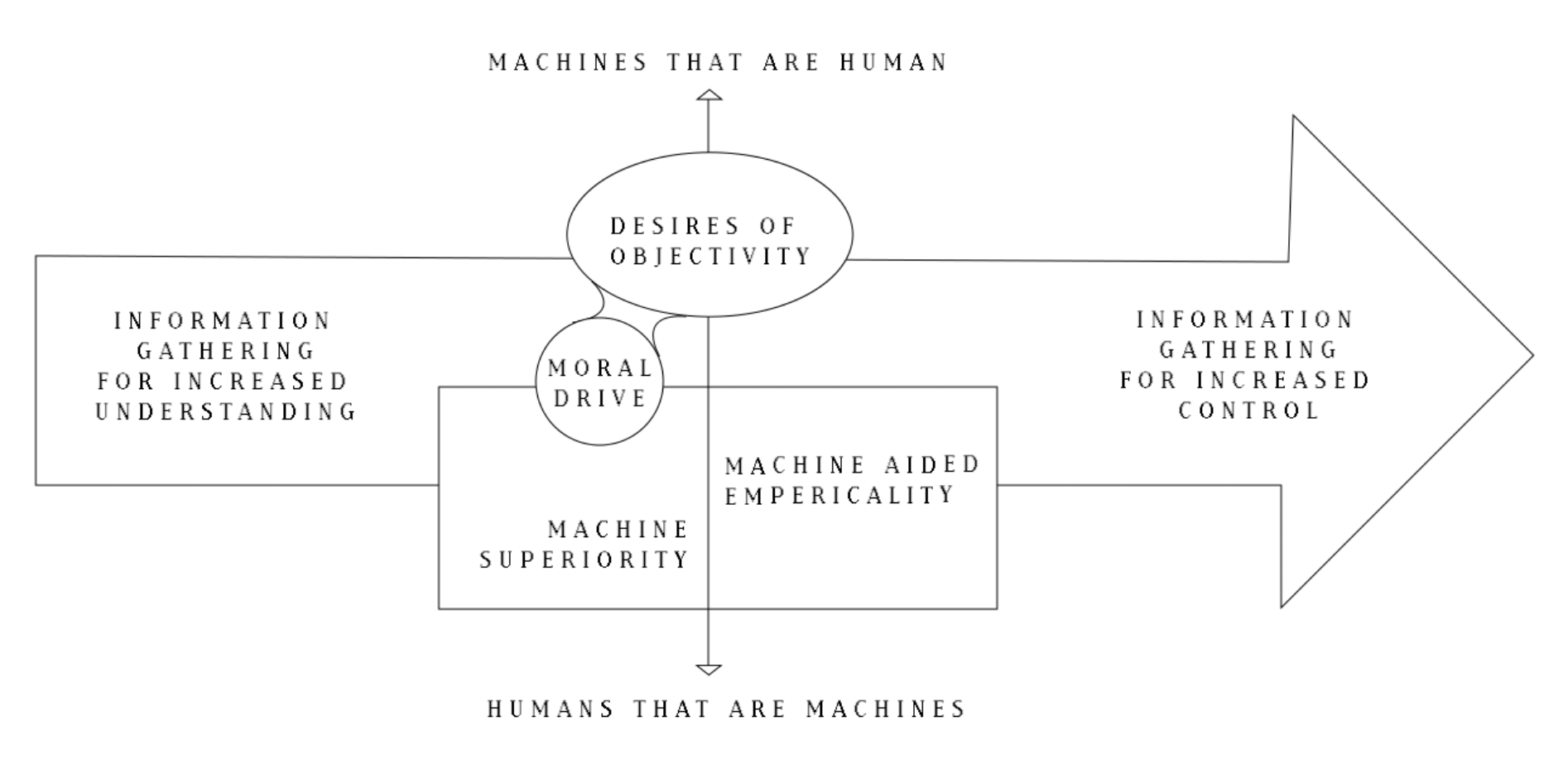

Desire to understand the world around us is one of the first relationships we enter as humans. However, underlying all this beauty of sensitivity and expression is the pure necessity of information. As Charles Eames states, "Beyond the age of information is the age of choices." We know very well that the key to having increased choice and control over our lives is to gather information that we previously did not have. Information is indeed power. Our desire to collect and organize the information around us encapsulates aspects of our lives we previously did not have enough control over: natural trends, the quantification of property and goods, processing efficiency, human behavior, the list goes on. In this section I will be exploring our modern habit of documentation through data collection –understanding where and why a seemingly innocuous habit, exacerbated by technology, continues to paint a murky future for us. I will be assessing why we value data, data creation, data storage, and how the ways in which these systems operate affect users in turn.

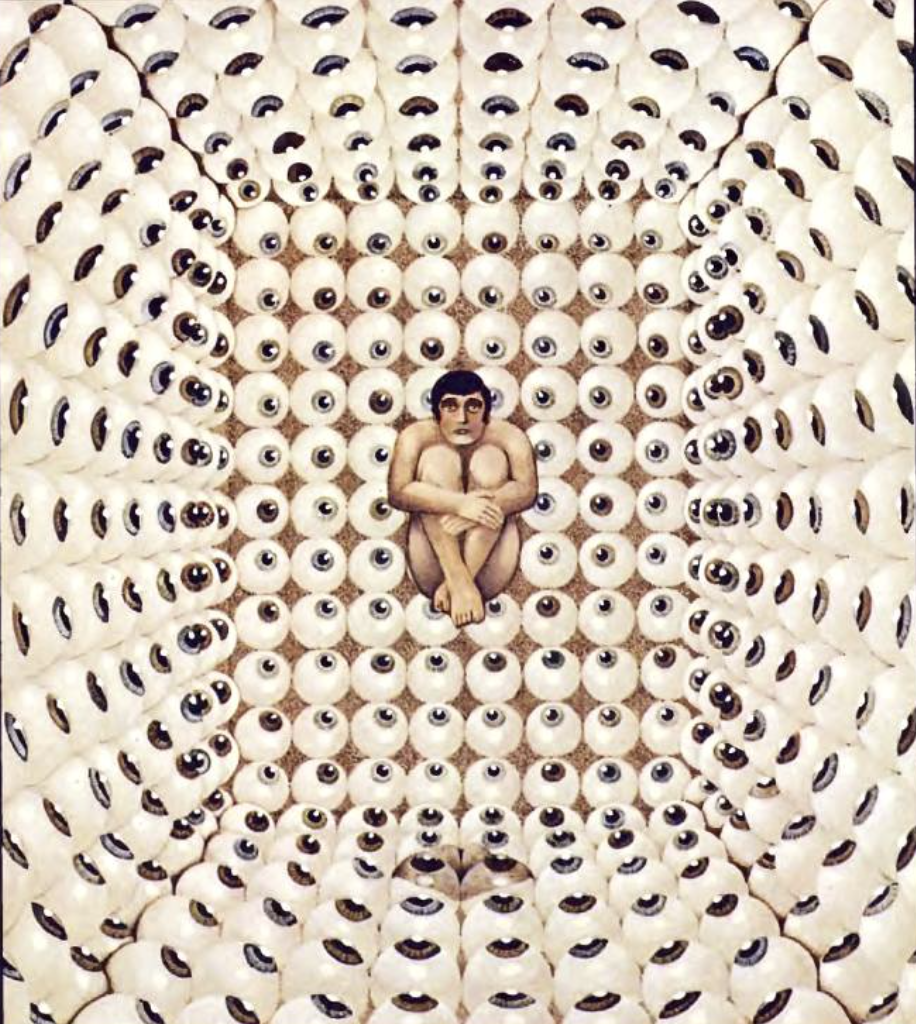

"Vision in this technological feast becomes unregulated gluttony." - Donna Haraway

Data collection is a long standing practice – in order to understand our relationship with data, we must think about why objectivity is valuable to us in the first place. One does not have to look very hard to see the importance of an empirical mindframe: whether it is applied to research, large scale decision making, or even personal matters. However, in the words of science historians, Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison: Western "history of the various forms of objectivity might be told as how, why, and when various forms of subjectivity came to be seen as dangerously subjective" The danger here is not just misinformation, as one might expect, but instead it is perception of self. Epistemology has a long and ever-expanding history– but Daston and Galison’s specific account of nineteenth century atlas makers (the time’s pinnacle data analyzers and visualizers) striving to achieve objectivity with newfound technologies of precision (machines, photos, and digital images) was said to be "a struggle of inward temptation." This specific point in history, I argue, encapsulates and exemplifies the growing dissonance we witness today between information gathering for deeper understanding of the world and those around us, versus information gathering to grapple with control and dissatisfaction of self-image: resulting in dissatisfaction and desire for control of that around us.

It is stated that the moral remedies these atlas makers sought "were those of self-restraint [...]. Seventeenth century epistemology aspired to the viewpoint of angels; nineteenth century objectivity aspired to the self-discipline of saints." Based on this information, it could be said that a researcher has a natural inclination to assess its current processes for fault, and develop new ways to counteract inadequate methodologies. While this is most definitely true in select cases, it should also be noted that this moral aspect of objectivity is a landmark where we can begin to see feelings of dissatisfaction drive our actions. Throughout science we continue to see the value in meticulous objectivity which requires painstaking, "care and exactitude, infinite patience, unflagging perseverance, preternatural sensory acuity, and an insatiable appetite for work" rather than the temptations of subjectivity, considering it unpredictable, wild, messy and immaturity. The article states, "it is [...] a profoundly moralized vision, of self-command trumping over the temptations and fragilities of flesh and spirit." Thus, as we strive towards this ideal image of the perfect observer, we run away from anything less than what may paint us as unyielding angels, saints, and now cyborg patriots of objectivity.

Machine objectivity ——————————————————————————————————————

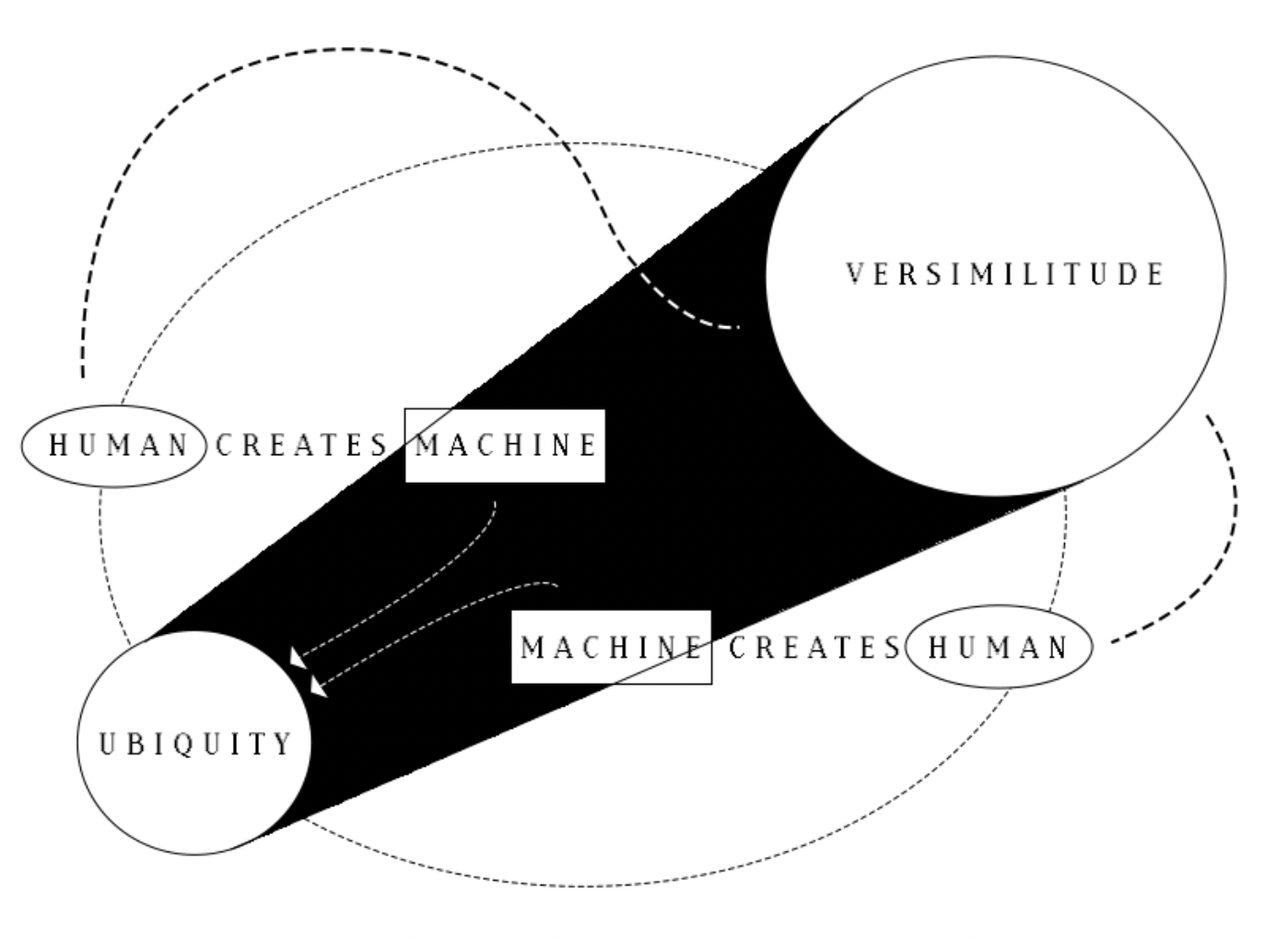

It was, of course, convenient and critical that at this time machines were increasingly becoming more and more relevant in research and documentation. Tools such as photographs, mechanically drawn images, polygraphs, and others made it,"nineteenth century commonplace that machines were paragons of certain human virtues. Chief among these virtues were those associated with work: patience, indefatigable, ever alert machines would relieve human workers whose attention wandered, whose pace slackened, whose hand trembled. Scientists praised automatic recording devices and instruments in much the same terms. [...] It was not simply that these devices saved the labor of human observers; they surpassed human observers in the laboring virtues: they produced not just more observations but better observations"With that in mind, by taking the morality of objectivity and the usage of machines to aid in our self-image of pious documenters, all of our objectivity is steeped in this subjective need to be perfect, to evade any sense of unkempt perspective, as this would only diminish the perceived gain of choice and justification of control, that we obtain when gathering more knowledge. Information leads to the age of choice and subsequent control; Perceived objectivity and moral superiority leads to the justification of that control, with machines becoming our perfectionist scapegoats.

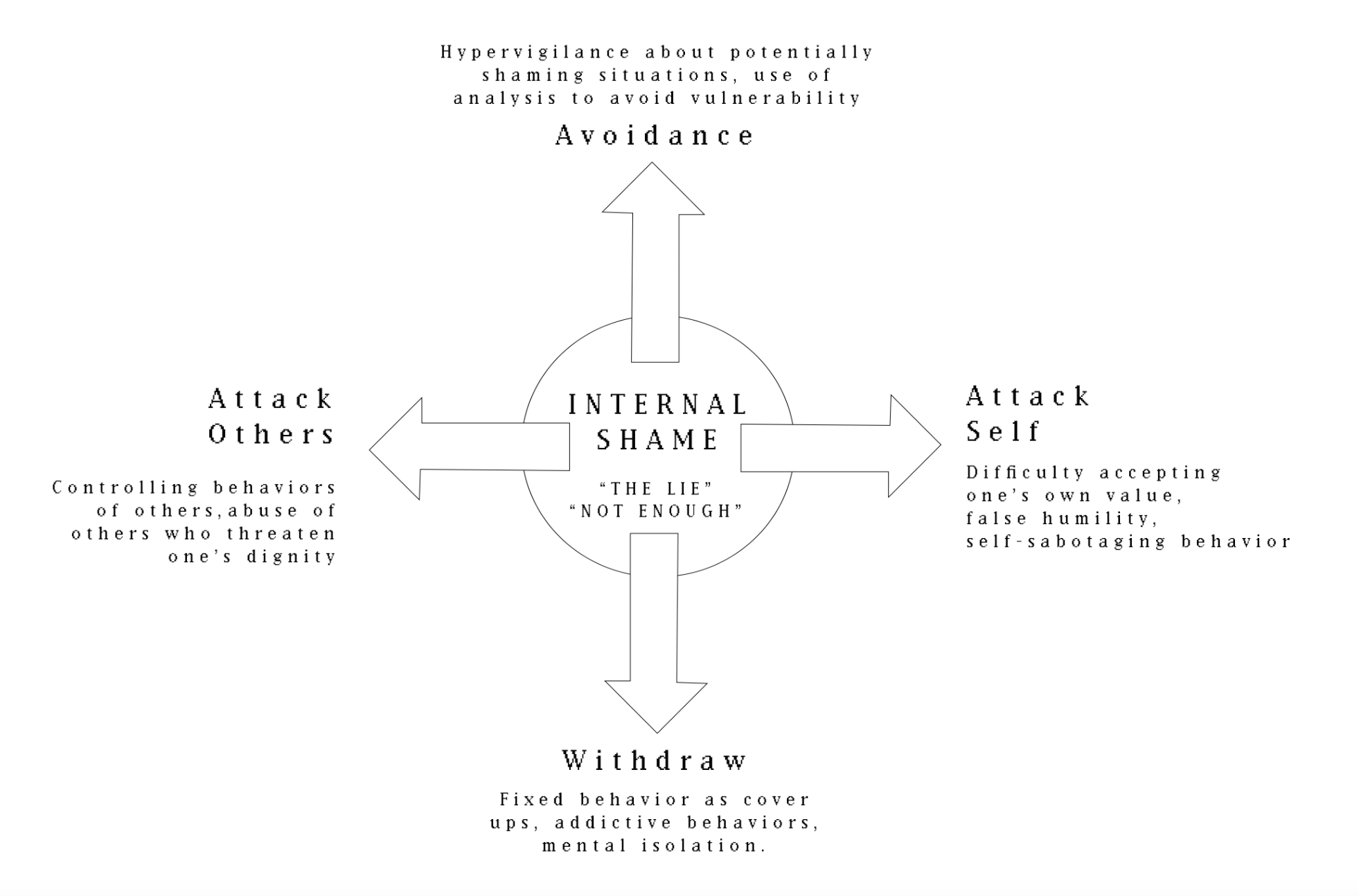

It is in this way that we’ve dismissed genuine and deep curiosity in the wake of ‘efficient perfection.’ Rather than turning towards the subjects we wish to understand, we turn away from them. We grab the information we want. Then, we use that information to cope with what our inner-self are dissatisfied with (namely self-perception and the perception of others). It is one thing when this mentality is applied to weather, or crops, or unknown specimens – but, when one abuses what is small and insignificant to them, it eventually becomes second nature to exert that behavior wherever one may get away with it. A true painstaking task is to dedicate yourself to understanding one person; It is a shortcut to single out one specific data point from one billion subjects, often fueling ego rather than understanding.

Visibility and Agency ——————————————————————————————————————

Data itself is not an evil entity. Neither is the act of collecting it, processing it, or utilizing it. Yet, the dangers and consequences of data collection can be seen right before our eyes. From headlines to word-of-mouth, to research papers and facebook group posts, it’s no secret that our day-to-day data is constantly being collected. It is skewed, gnarled, contorted and reduced– knowingly and unknowingly. This data spans from obvious things, such as social media activity and web browsing, to ‘big data’ breadcrumbs such as the geographic data off your credit card, home thermostats, smart devices, and more. These collection methods and processes exist in most crevices of our technology-dependent lives. Having started as surplus data solely for product improvement, to then become highly valued user behavior data in the age of surveillance capitalism, as coined by Professor Shoshanna Zuboff, which "unilaterally claims human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioral data."In our efforts to collect and document our lives and the lives of people around us, it seems it has been forgotten that, "knowing and being known is a mutual exchange," not something that can or should be done as a mechanical and removed observer. Now, we can start to see where this untethered dissatisfaction on the data collectors side is not isolated to themselves, instead it very directly can be seen seeping into the experiences of the user. The unequal positioning of the observer (data collectors) and the observed (technology user) is only one point in which shame can appear. There is an inherent lack of trust that the observer will accurately understand their subject. As Microsoft researchers Kate Crawford and Danah Boyd state: "There is a considerable difference between being in public and being public, which is rarely acknowledged by Big Data researchers." It is exactly here where technology incites shame as, "to be seen in a certain light carries the risk of feeling shame [if] invisibility has been foreclosed." Not only does this mentality set our technologies up for failure of empathy, technology users are the ones facing real consequences of innovator ego and ideals.

This messy amalgamation of modern-day documentation has resulted in hyperfocusing on specific bits of information (data bias), and the neurotic documentation of data (technology’s memory) – based upon the focal points of those in power, who want to stay in power. As Manovich writes, there are "three classes of people in the realm of Big Data: ‘those who create data, [...] those who have the means to collect it, and those who have expertise to analyze it.’" Data collection is a practice that should lead us to the improvement of our lives and the lives of the people around us. In many ways it has – However, it does not take one long for one to see that this is often not the case.

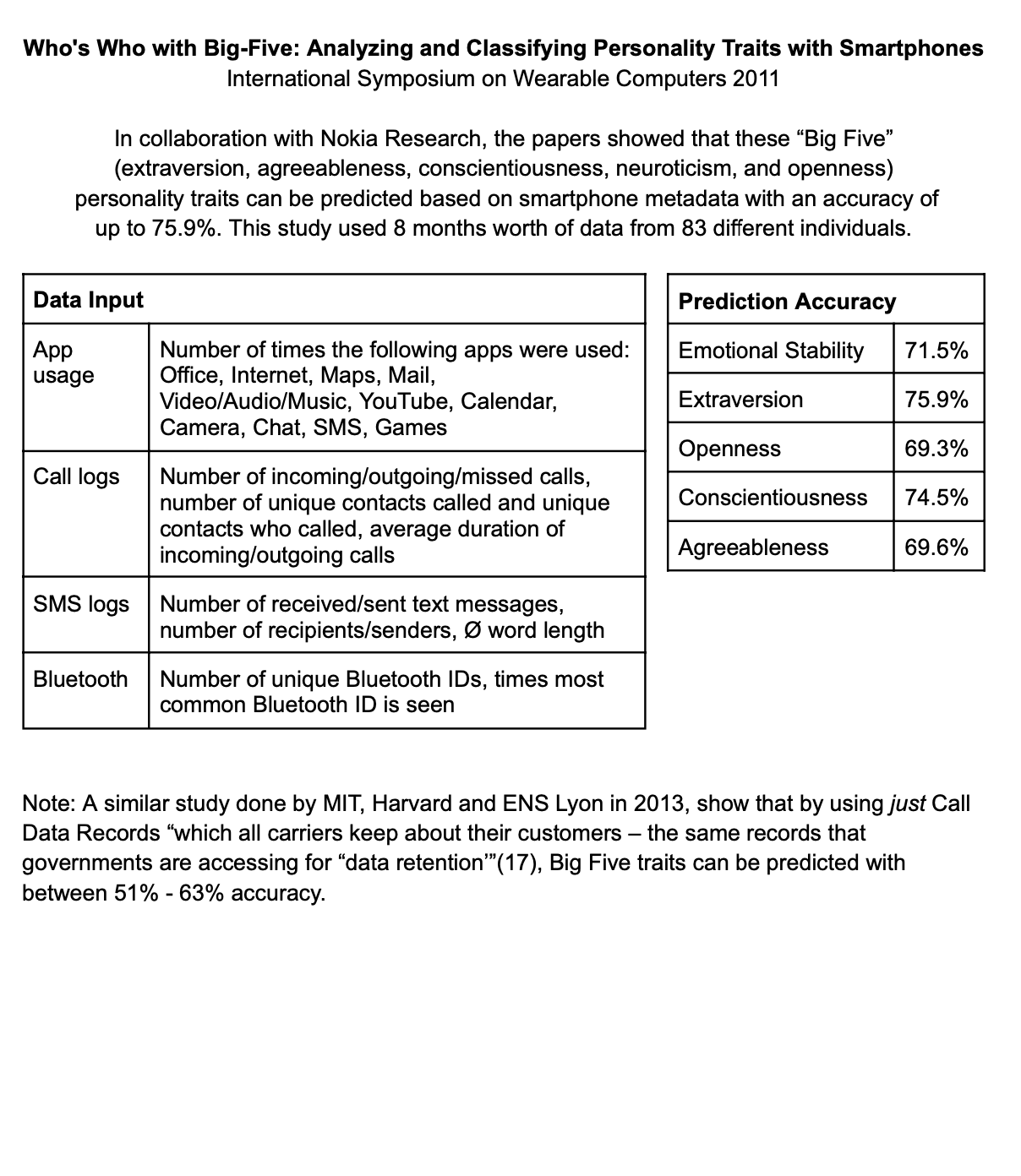

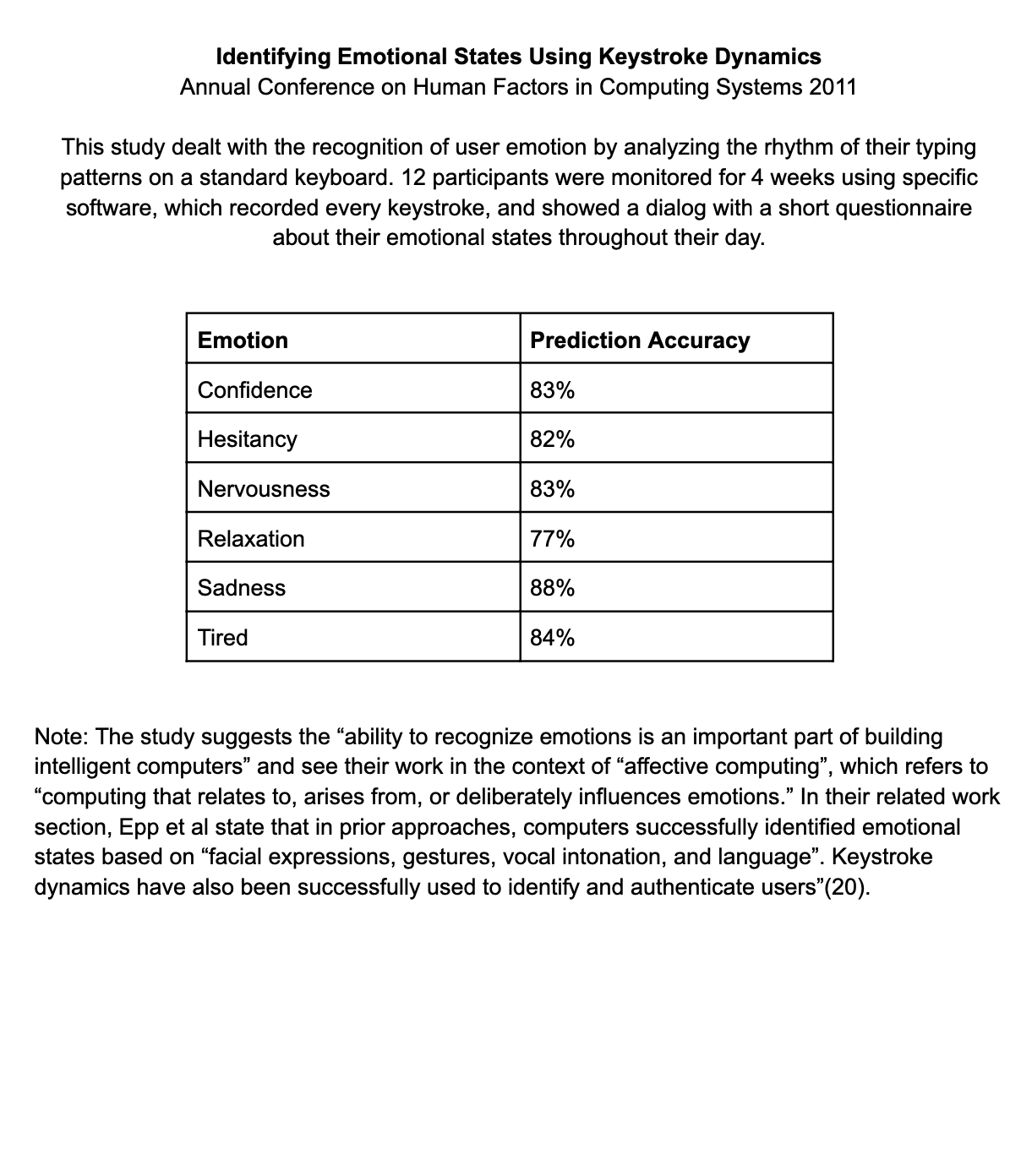

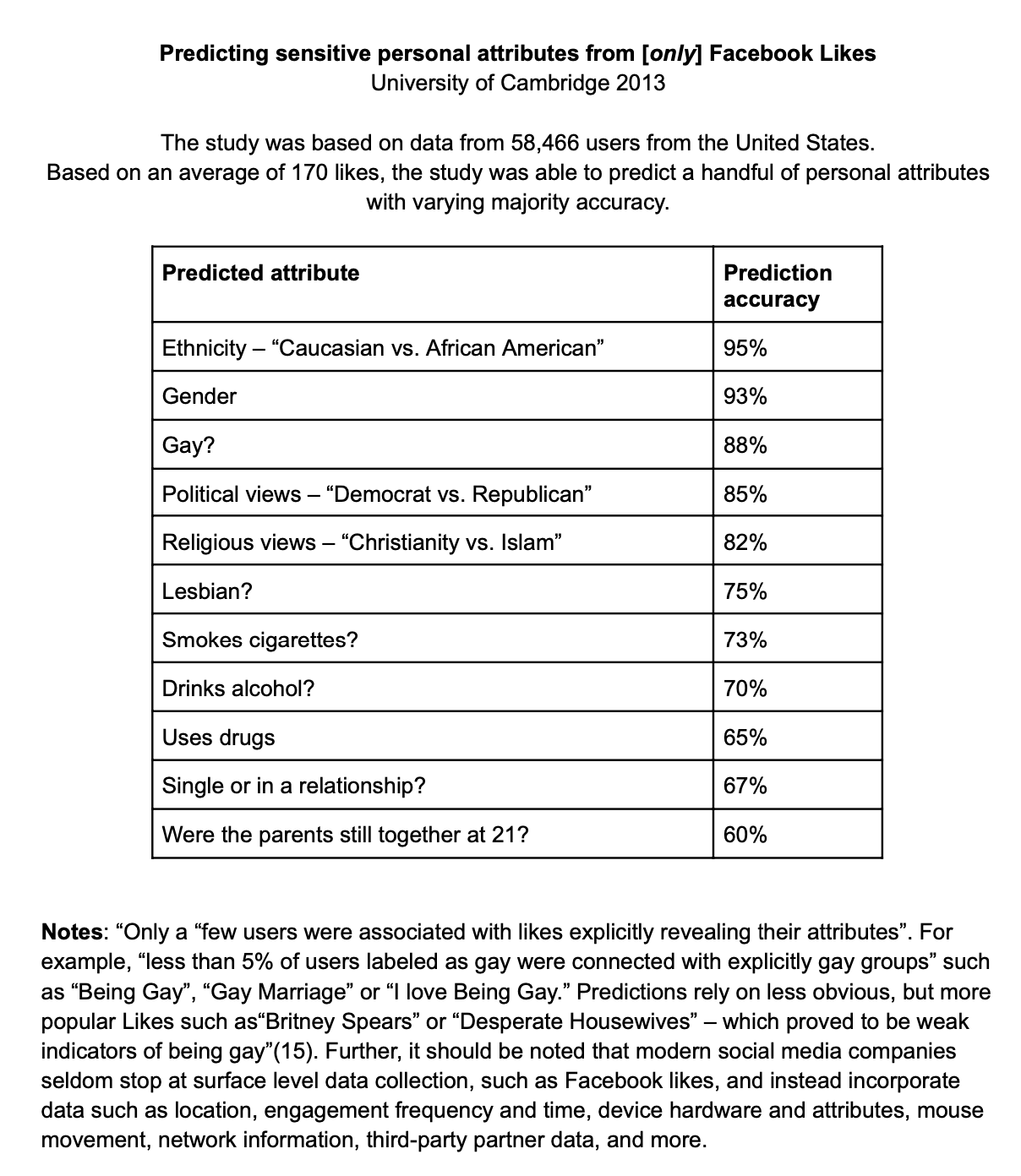

As Daston and Galison state, machines are "patient and exact observers, blessed with sense more numerous and more perfect than our own, they work by themselves for the edification of science; they accumulate documents of an unimpeachable fidelity, which the mind easily grasps, making comparisons easy and memory enduring."The extent to which these data practices are continually and more pervasively being used only increases by the day. All of this information merely and briefly demonstrates the pervasiveness and capabilities of user data analysis. These technological feats, if standing by themselves, could illustrate a technologically competent and able future. However, the political and economic environment that these technological capabilities reside in, raise concern in a multitude of ways.

In the article "The Clocks Are Striking Thirteen," the author expresses the collective concern that there are numerous accounts of the Supreme Court largely overlooking the fourth amendment in lieu of modern-day ‘digital searches.’ They state, "when the government buys broker data without probable cause, it flouts our supermajority grant, surreptitiously subjects blameless citizens to "near perfect surveillance." Without the fourth amendment being wielded in the valid context of digital privacy, an increasing number of government abuse cases can be seen. This article was written just in 2024, and since then, the concerns raised have become evermore troubling in recent times.As recent current day events such as fluctuating immigration policy, increasing censorship, women’s reproductive rights, gender orientation and more, the overlooking of the Fourth Amendment has the potential to put many citizens at risk, "recklessly expos[ing us to the possibility of] stalking, harassment, blackmail, public shaming, and arbitrary persecution for our familial, political, professional, religious, and sexual associations." Technology seldom resembles a tool for understanding anymore, instead acting as a tool of highly subjective control and exploitation.

Technology’s memory —————————————————————————————————————

Just as data collection itself grapples with ideals of unyielding perfection, so too does technology’s memory. It’s no news that digital storage capabilities have revolutionized communication and systems of information, allowing for greater information accessibility and preservation. Technologies of storage are often viewed as extensions of our human brain. And further, as stated within the article ‘Technologies of Memory,’ "Embedded within much technological discourse is a Utopian, techno-centric belief in an infallible memory-machine, in contrast to a notionally capricious, context-dependent and therefore fallible human memory." However, it is quite common knowledge at this point that digital storage is both a prevalent blessing and curse. Once something has been released onto the internet, it is near impossible to erase. Even if it were to be erased, as legislation is currently attempting, the act of getting it erased likely only adds to the issue via the Streisand Effect: "trying to suppress information can backfire by drawing attention to the information you are trying to suppress." Not to mention other implications of such an act if it is not properly formatted to prevent abuse of it.

With these daunting aspects in mind, coupled with knowing most user data is constantly being collected unknowingly, one could draw connections between the internet’s memory capacity and being aware of one’s own limitations in the presence of a seemingly omnipotent digital entity. Ubel states, "it was Nietzsche (1966b), whose parable of the Ugliest Man in Thus Spoke Zarathustra Tillich references, who averred that the very notion of an all-seeing God contributes to the production of shame." While it’s a bold statement to claim that digital memory could be compared to an all-seeing G-d, the effects of having media uploaded online, whether it be pictures, videos, text, audio, etc. creates a relationship between user and device where the user loses a major amount of agency and control. All the while also increasing feelings of being observed and scrutinized – with the very real possibility of it being used against you and outwardly condemned. The elusivity of expressing/exposing yourself and your identity through media and not knowing how it’s being used, viewed, or perceived can cause tantamount uncertainty and shame. Moreover, in the case of technology’s memory, the near-permanent aspect of the internet’s memory results in a sense of disintegrative shame. Disintegrative shame is characterized by a permanence aspect (i.e. branding or maiming), this permanence leaves no room for redemption, as opposed to reintegrative shame which "does not push the shamed toward even worse patterns of behavior,’ it does not isolate individuals, and it ‘allows individuals to hold themselves accountable through the actions of others.’" It’s not difficult to think of an example on the internet where an individual is canceled or ridiculed for any one aspect of their being. As Sheila Brown, author of ‘The Criminology of Hybrids: Rethinking Crime and Law in Technosocial Networks’, states, "... endlessly circulating, shifting, pixels affect real lives … real humiliations and human pains are generated; and real relations of (patriarchal) power and exploitation are reproduced and reinforced."

Technology’s superior capacity for information storage is undeniable– so much so that humans increasingly rely on digital memory as an extension of their own. While a large aspect of digital storage is its superior capabilities that far exceed that of its human creators, the way in which these technologies are developed take major influence from human behavior and cognition. For example, the term ‘contextual computing’ refers to, "[using] time, location and personal rhythm, task or activity, along with models of human memory practices, to help people manage their everyday lives via information storage and/or reminder." On a more direct level, organizations such as IBM’s Cognitive Computing group and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have been developing artificial human brains, creating brain-inspired computers to "build an efficient [artificial] memory system [...] inspired by how the brain actually works, [imitating] the plasticity of human synapses over time." Similarly, modern day artificial intelligence uses ‘neural networks,’ often understood to be modeled after the organization of the human brain. However, one MIT news article urges people caution when comparing the human brain to neural networks as, "computing systems that appear to generate brain-like activity may be the result of researchers guiding them to a specific outcome." Again, we continue to see this recurring theme of machine ability being ‘objectively’ superior to human ability, fueling the cycle of untethered dissatisfactions for innovators, and negatively affecting users in turn– all facilitated by a machine that attempts to obscure allegations of subjectivity.

While the internet has a seemingly limitless capacity to store information, it can be seen that storage (just like human memory) is not a passive thing, as "what is remembered individually and collectively depends in part on technologies of memory and the associated socio-technical practices, which are changing radically." Storage, while all-seeing, is still biased: it’s a "constant negotiation of determining value and worth of information and archiving and forgetting that which might be important but not needed." Coupling this information with the fact we’ve come to rely on technological memory as an extension of our own, technologies of information flows should not be perceived as objective, or matter-of-fact. As our technologies become increasingly more obfuscated about how they handle data storage and circulation, the digital world becomes a breeding ground for uncertainty, distrust and judgment.

Implications and Adding Humility ————————————————————————————

What’s been spoken about so far hardly even touches the surface of the shameful and aggressive nature of interacting with technology on a personal level. Cathy O'Neil, author of the novel, "The Shame Machine: Who Profits in the Age of Humiliation" states: "By pitting us against each other in these endless shame spirals, Big Tech has successfully prevented us from building solidarity and punching up against the actual enemy, which is them. The first step is for us to critically observe their manipulations and call them what they are: shame machines." Social technologies should be "a story about establishing and nurturing personal connections at scale." Yet this is seemingly not the case. As Natalie Wynn, creator of the YouTube channel ‘ContraPoints’, puts it, social media is "... a habit that is making me hate myself, and it's making me unfairly contemptuous towards others." Shame has immense power to positively impact a community and regulate social behavior based upon the collective values; Yet social media is often seen to be unproductive at best, and disintegrative at worst.

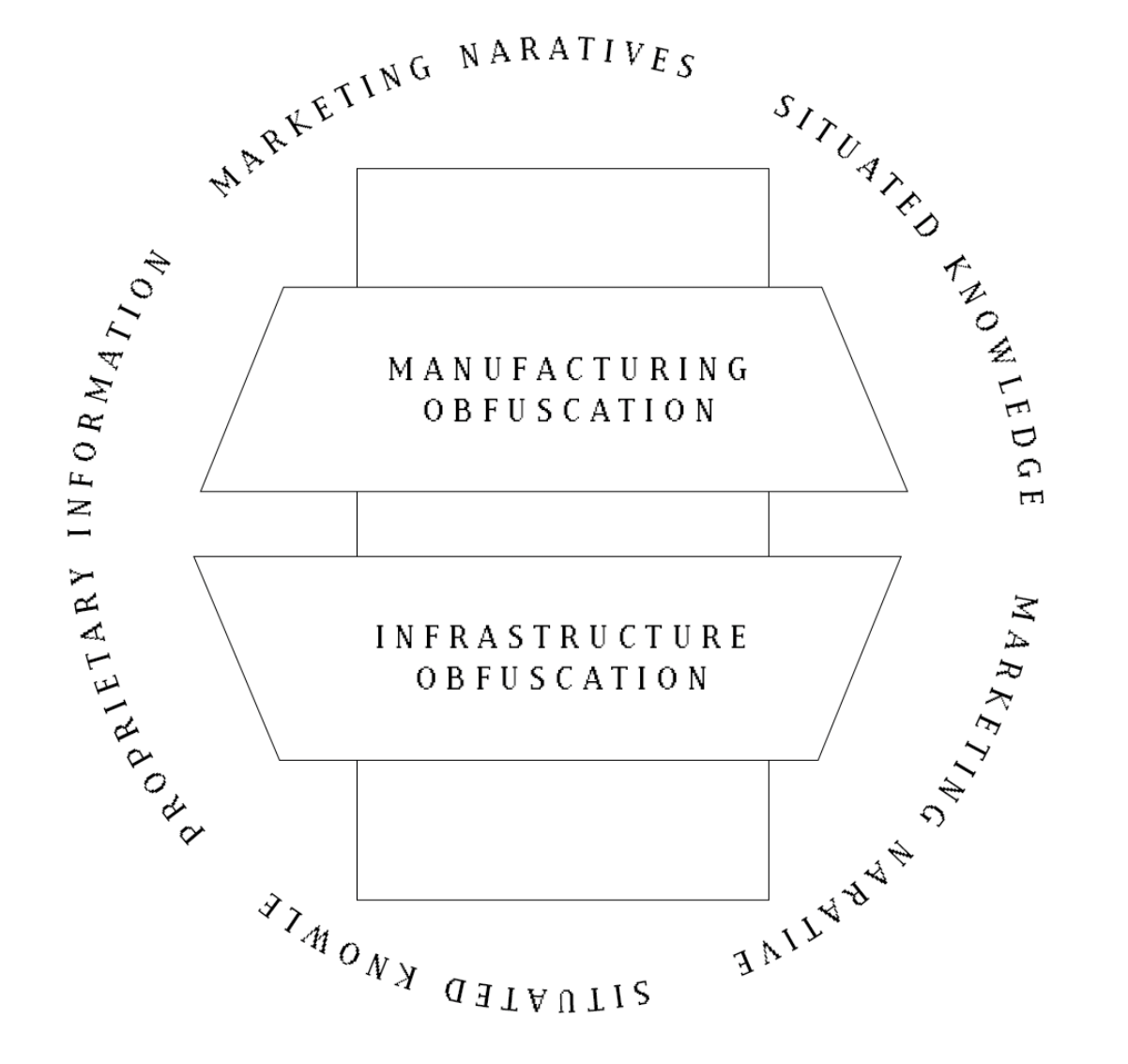

To conclude, a key point I’d specifically like to call attention to is the comparability between the mechanics of control and shame. Both hold the key to agency, for users and innovators alike. Likewise, both hinge on the presence of visibility (internal or external): "Visibility, and the control it allows, defines all work sites, regardless of what is being manufactured or supplied. Vision is power, and infrastructure is built for and by a world that believes in this philosophy: its image is carefully controlled and constructed, and the capacity for watching and being watched becomes its own infrastructure." If information is key to choice and subsequent control, we can begin to see the slippery slope that these elements lie upon, resulting in neurotic documentation of data, and hyperfocusing on specific points based on the focals points of those in power, who want to stay in power. This issue of power is one that is not new nor novel, as Alexander Stein puts it, the unfortunate truth of this reality is that trying to change the wrong-doer is often futile. However, we can instead aim our focus on those who are not consciously falling prey to the systems in place, and those who are willing to implement smaller scale experimentation, research, and solutions. By acknowledging the presence of shame within our technologies, we can start to better understand why technologies that set out with good intentions, may turn sour, driving us further and further away from ourselves and initial goals.